The days when you could walk out of the Louvre with the Mona Lisa under your arm are over. There are all sorts of safeguards now—electric eyes, pressure sensors, lasers, which in the movies at least, must usually be overcome by dangling the thieves from the ceiling. I love art-heist stories. They always pose a question: what’s real and what’s fake? What’s the difference between an original and a copy? They also sketch out over the years not only a change in technology but a change in ethics. Here are five of my favorites.

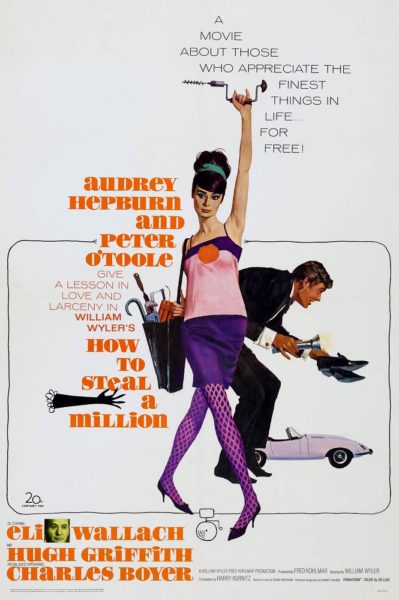

How to Steal a Million–1966

We start with the soufflé, extremely light, and, as you would expect of any film starring Peter O’Toole and Audrey Hepburn. It just oozes charm. Surprisingly, under its candy coating, it also oozes authenticity. The forger(Hugh Griffiths, Hepburn’s papa) has made certain to dig up authentic dirt from Arles to add to his Van Gogh forgery. And it takes only a chip of paint from said forgery undergoing chemical analysis to prove it’s a fake. And it’s the forger’s hubris that places him in danger, which is often the case in real life, where it’s the risk of being discovered that is often a forger’s prime motivation. In this case, the forger has loaned a forged Cellini Venus (done by his papa, with his mother as the model—it’s the family business) to a museum—which now awaits scientific authentication for insurance purposes, which well spell ruin. Therefore, Hepburn and O’Toole must steal it. Take note of the high tech used: a magnet, a boomerang and a bucket. Also, take note of the ethics: O’Toole is actually an insurance investigator (which profession often enters into these stories), so he’s only along for the ride because he’s in love with Hepburn and he wants to shut down Papa’s operation. Note the end twist, a staple of heist movies. Papa is allowed one last con. Finally, note the equation of the living female form with the art object. Hepburn’s resemblance to the Venus is duly noted.

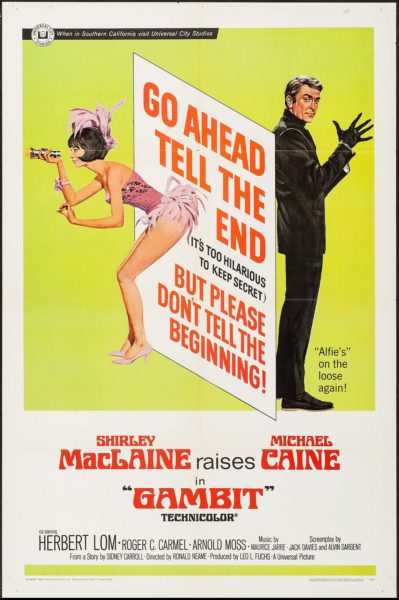

Gambit—1966

Here is where the equation between female and objet d’art is made exact, as the richest man in the world holds a bust of a Chinese empress who exactly resembles his late wife, and also resembles the thieves’ bait—in the form of Shirley MacLaine. The first half-hour of the film is a sort of fantasia. We see the perfect heist with MacLaine absolutely silent—and rigidly regal as a statue. But it is Michael Caine’s fantasy to steal the statue, and in real life, MacLaine is annoyingly chatty—but also far more cunning and take-charge than Caine’s character. Once again, it’s an electric eye that must be defeated—this time by going in from above. Once again, Hollywood’s middle-class morality is satisfied when it’s discovered that the plot was never to actually steal the statue—and roguishness is satisfied when it’s revealed just how many copies of the statue have been made.

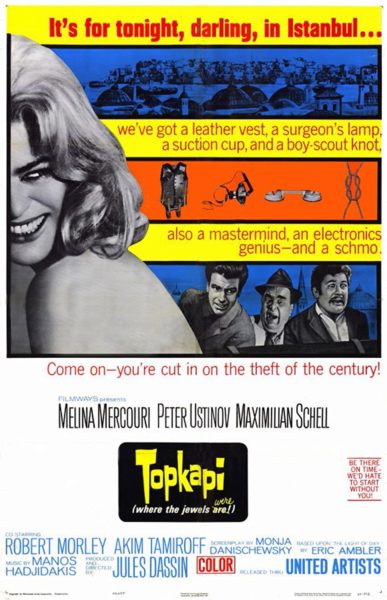

Topkapi–1964

TOPKAPI is loose, as if the heist movie had taken off its corset. No hiding from the audience. Melina Mercouri tells us up front that she is a thief and she wants to steal a jewel-encrusted dagger–and she’s something of a dagger herself. indeed, it’s her powers of seduction that keep the entire gang in line .Any follower of the “Oceans “movies knows you need professionals to pull off a heist. But Maximillian Schell, her paramour, chooses amateurs to steal the dagger from an Istanbul museum. And because the driver selected is the bumbling uber-amateur Peter Ustinov, Turkish security are on their trail almost from the beginning—although neither he nor they have any idea what the gang is up to. As Ustinov he gets drawn further and further into the plot the mistakes tend to mount up each one dealt with by Schell’s mercurial genius. Though the heist goes off flawlessly, all their plans come to naught when a little birdie tells Turkish security where to look. The final twist—even in prison, Mercouri is plotting the next heist.

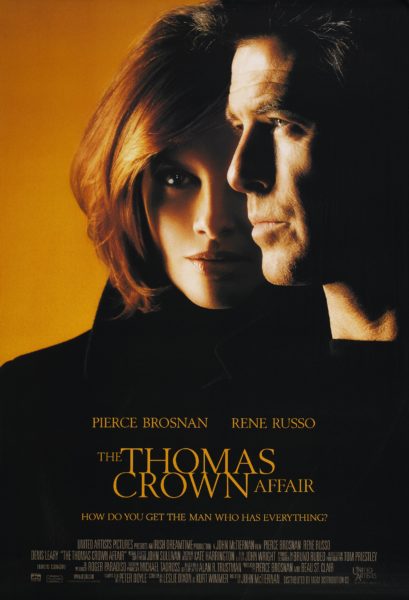

The Thomas Crown Affair—1999

This movie gets high marks for flash and dash. Bhat you have to keep in mind is that the nineties was the apex of CEO hero worship. He’s bored, he takes huge risks for kicks. If this movie had been made twenty years later (and, yes, there’s a remake in the works), he’d be building space rockets. This heist is so expensive and stuffed with so many high-tech gadgets that money is no object when it comes to style points. But the moral of the story is revealed early on, when a schoolteacher regales her bored class with this bit of info about the Monet they’re viewing:

“Try this. It’s worth a hundred million bucks.”

The thief’s up against an equally world-weary insurance investigator, whom he proceeds to seduce. The movie tries to have it both ways. In this one there’s a curve ball: it’s the male of the species is equated with the art object. They try to portray Crown as the anonymous businessman of a Magritte painting. Yet his money makes him anything but anonymous. Of course, the painting was never actually stolen. But in the twist, he steals a Van Gogh to charm his lady. Mixed message there.

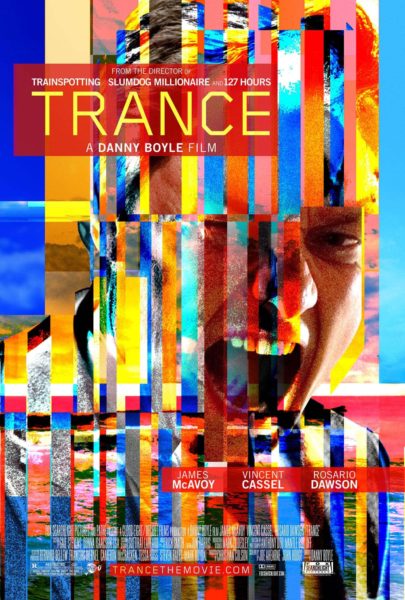

Trance—2013

Violence—and revenge—come to the heist movie. There’s no finesse in stealing this Goya—or so it would seem. A gang of thieves raids an art auction, causing chaos. James McAvoy, the auctioneer attempts to get the Goya to safety, but for his troubles gets clocked by the gang’s leader, and winds up with a case of selective amnesia: he can’t remember where he hid the painting. And since he’s secretly part of the gang, this is not acceptable. They try torture first, then bring in a hypnotist. But the hypnotist, Rosario Dawson, has her own agenda. This is really a complex heist, with enough twists and turns and hypnotic episodes to confuse the most attentive audience member, so I won’t spoil this one for you. But is the substitution of revenge for roguishness really what the genre wants? The final twist: most of the players are dead by the end.

For every generation, the heist movie is a reflection of the generation’s preoccupation. Maybe we’ll see a film soon where the motivation is that baby needs new shoes.

THE STRANGE CASE OF THE DUTCH PAINTER by Timothy Miller

Paris, 1890. When Sherlock Holmes finds himself chasing an art dealer through the streets of Paris, he’s certain he’s smoked out one of the principals of a cunning forgery ring responsible for the theft of some of the Louvre’s greatest masterpieces. But for once, Holmes is dead wrong.

He doesn’t know that the dealer, Theo Van Gogh, is rushing to the side of his brother, who lies dying of a gunshot wound in Auvers. He doesn’t know that the dealer’s brother is a penniless misfit artist named Vincent, known to few and mourned by even fewer.

Officialdom pronounces the death a suicide, but a few minutes at the scene convinces Holmes it was murder. And he’s bulldog-determined to discover why a penniless painter who harmed no one had to be killed–and who killed him. Who could profit from Vincent’s death? How is the murder entwined with his own forgery investigation?

Holmes must retrace the last months of Vincent’s life, testing his mettle against men like the brutal Paul Gauguin and the secretive Toulouse-Lautrec, all the while searching for the girl Olympia, whom Vincent named with his dying breath. She can provide the truth, but can anyone provide the proof? From the madhouse of St. Remy to the rooftops of Paris, Holmes hunts a killer—while the killer hunts him.

Mystery Historical [Seventh Street Books, On Sale: February 1, 2022, Paperback / e-Book, ISBN: 9781645060420 / eISBN: 9781645060437]

About Timothy Miller

Timothy Miller is a native of Louisiana, a graduate of Loyola University in New Orleans. He has directed and designed lighting for plays in New Orleans and Chicago. His short play “Bumped” was filmed as “Scanned” starring David Jensen, and the feature film of his script “At War with the Ants” won a Silver Remi Award at Houston’s Worldfest. His screenplays have placed in several contests, including five times as a semifinalist in the Academy’s prestigious Nicholl Fellowship. He has taught English in Milan and has written for the Italian design magazine Glass Style. He tended bar for twenty-five years in New Orleans, Houston, Chicago. And San Francisco. When not mourning over his beloved New Orleans Saints he is mourning over his beloved Chicago Cubs. His favorite superhero is Underdog.

No Comments

Comments are closed.