Dialogue is an ancient Greek stage direction, meaning “action through words.” One of the first critiques I got from an agent, looking at my neatly printed manuscript was “There’s not enough white space,” meaning there was too much narrative description, and not enough dialogue.

Dialogue opens up the tightknit block of words we are accustomed to in textbooks and allows your story to breathe through verbal exchanges between your characters. Frequent doses of white space make your work less intimidating and helps your reader speed along through your story.

Dialogue is used to accomplish three things: Exposition, to reveal character, and to provoke an action. Let’s look at these in turn.

Exposition. I write historical fiction, so putting my reader into an unknown universe and making them quickly comfortable there requires that I give them a sense of time and place, but without the dreaded “Info Dump.” So how do I do that? I incorporate the information transfer into as graphic a manner as possible. In my first novel, A Knife in the Fog, my heroine, Margaret Harkness, is a female author from a proper middle-class British family temporarily living in Whitechapel to do research on her novels. As she takes my narrator, Arthur Conan Doyle, on a tour of Whitechapel, I interspace her narrative describing the conditions in that neighborhood with Doyle’s own observations, reinforcing her comments while giving the reader strong visual scenes that bring her words to life. By the time they reach their destination, a site where Jack the Ripper killed one of his early victims, the reader is primed for the violence soon to follow.

In one of my early and most difficult scenes, I have Doyle meet with the Scotland Yard Inspector leading the hunt for Jack the Ripper. He has a lot of crucial information I need to slip into the reader’s mind as painlessly as possible so that the rest of the story makes sense. To keep the Inspector from giving my hero a monologue I intersperse questions, requests for clarification, and brief descriptions of the Inspector in various stages of lighting his pipe and sending smoke up to the ceiling, (an example of dialogue provoking action).

Characterization. The vocabulary a character uses needs to be carefully considered. Any character with more than one scene gets a biography of some kind in my story bible, a summary of the major characters and the historical period I can refer to quickly as I work through my story. The words used should befit their education and station in life, and the tone consistent with the situation and their relationship to the person they are talking to.

On that same walking tour Margaret gives to a very proper Conan Doyle, she at one point refers to the streetwalkers using back yards and stairwells for a “Four-Penny Knee Trembler,” which so shocks Doyle he nearly comes to a dead halt as they walk through Whitechapel. Margaret’s casual use of the term while otherwise speaking in the proper tone of a lady of her class, tells you much about how she has come to terms with her environment, while Doyle’s reaction tells you much about him as well.

To provoke action. Much of human conversation is conducted nonverbally through facial expressions and body movements. To avoid your dialogue from becoming verbal tennis matches, intersperse them with small actions to give the reader an image to tie to the words, such as my pipe-lighting Inspector.

The action should be consistent with the situation and the character’s motivation at the time, it can’t be random, but with a good imagination you can come up with enough variety to keep the words fresh.

My final comment is not something you’ll see in any books on writing, but something I discovered on my own. I have three main characters in my novel, Doyle, Miss Harkness, and Professor Joseph Bell, the real-life inspiration for Sherlock Holmes. I wish I was this clever, to begin with, but as I completed my novel I realized that I’d ascribed to each of them one aspect of personality.

Doyle is pure Ego. A proper British gentleman, the peas could not touch the carrots. Bell is Super-Ego. He understood the need for rules but could see the larger picture, so also knew when the rules should be ignored. Margaret is pure Id. She says what she thinks as soon as she thinks it, and is basically the person it requires two to three stiff drinks for most of us to become. I found that dialogues with the three of them challenging to write, but engaging. Having a third person active in the conversation created an inherent tension and kept my readers engaged, wondering what would happen next.

Try it, and see if it works for you.

By the way, it is a rare thing if a dialogue only reveals character, provides exposition or provokes an action. A good dialogue usually does all three, thus provoking “actions through words.”

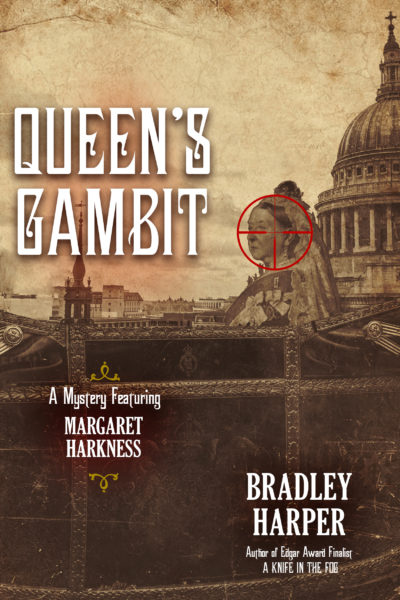

THE QUEEN’S GAMBIT by Bradley Harper

Margaret Harkness and Arthur Conan Doyle #2

Spring, 1897. London. Margaret Harkness, now in her early forties, must leave England for her health but lacks the funds. A letter arrives from her old friend Professor Bell, her old comrade in the hunt for Jack the Ripper and the real-life inspiration for Sherlock Homes. Bell invites her to join him in Germany on a mysterious mission for the German government involving the loss of state secrets to Anarchists. The resolution of this commission leads to her being stalked through the streets of London by a vengeful man armed with a powerful and nearly silent air rifle who has both Margaret and Queen Victoria in his sights. Margaret finds allies in Inspector James Ethington of Scotland Yard and his fifteen-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, who aspires to follow in Margaret’s cross-dressing footsteps.

The hunt is on, but who is the hunter, and who the hunted as the day approaches for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee when the aged empress will sit in her open carriage at the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral? The entire British Empire holds its breath as the assassin, Margaret, and the Queen herself play for the highest of stakes with the Queen’s Gambit.

Mystery Historical [Seventh Street Books, On Sale: September 17, 2019, Paperback / e-Book, ISBN: 9781645060017 / eISBN: 9781645060079]

Buy THE QUEEN’S GAMBIT: Amazon.com | Kindle

| BN.com | Apple Books | Kobo | Google Play | Powell’s Books | Books-A-Million | Indiebound | Ripped Bodice | Amazon CA | Amazon UK | Amazon DE | Amazon FR

About Bradley Harper

Bradley Harper is a retired US Army Colonel and pathologist who has performed over two-hundred autopsies and some twenty forensic investigations. A life-long fan of Sherlock Holmes, he did intensive research for this debut novel, A Knife in the Fog, including a trip to London’s East End with noted Jack the Ripper historian Richard Jones. Harper’s first novel was published in October 2018 and was a finalist for a 2019 Edgar Award by the Mystery Writers of America for Best First Novel by an American Author.

No Comments

Comments are closed.